An Author’s Mind: interviewing Jane Davis

Posted on February 21, 2018 by Elizabeth Gates

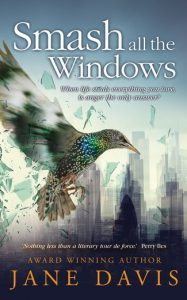

I am delighted to begin an occasional series today, entitled ‘An Author’s Mind’. In this, authors and I will be exploring the intellectual prompts – and the passions – that stimulate an Author’s Mind. Something that fascinates me is that authors, whether writers of contemporary or historical fiction, often ask the same questions although the answers can be so very different. And I am particularly pleased to begin the series with a peep at the latest contemporary fiction novel by award-winning novelist, Jane Davis. During the excitements of publishing Smash all the Windows, Jane agreed to be interviewed for The Wolf of Dalriada‘s blog and I hope you’ll enjoy her honest and thoughtful responses to a fellow novelist’s questions!

Welcome, Jane!

Can you briefly describe the story of Smash all the Windows?

For the families of the victims of the St Botolph and Old Billingsgate disaster, the undoing of a miscarriage of justice should be a cause for rejoicing. For more than thirteen years, the search for truth has eaten up everything. Marriages, families, health, careers and finances.

Finally, the coroner has ruled that the crowd did not contribute to their own deaths. Finally, now that lies have been unravelled and hypocrisies exposed, they can all get back to their lives.

If only it were that simple.

People say that all fiction is autobiographical. Have you based Smash all the Windows on a formative experience?

Actually, it was quite a recent experience! I think you always have to make it personal, so I combined two of my fears – travelling in rush hour by Tube, and escalators. Last year, I suffered a fall on my way to a book-reading in Covent Garden. I was overloaded, having just finished a day’s work in the city. I was carrying my laptop bag, my briefcase, plus a suitcase full of books. The escalator I would normally have used was out of order. Instead we were diverted to one that was obviously much steeper but I wasn’t prepared for how fast it was. I pushed my suitcase in front of me while holding onto the handle and stepped on. The case, which was only one step in front of my feet, literally dragged me off-balance. Fortunately, there was no one directly in front of me, and a few bruises and a pair of laddered lights aside, I escaped unscathed. But I can still blink and see the moment I knew I was about to fall and the recognition that there wasn’t a damned thing I could do about it.

What is the most significant event for you in the story of Smash all the Windowsand why?

In a way this was an odd piece of story-telling, because the reader knows right at the outset what the key event is. The St Botolph and Old Billingsgate disaster was a large-scale disaster that resulted in the death of fifty-eight commuters. The challenge was to show the impact of the event on different individuals and their families, who have re-lived it each day of the eighteen-month long inquest. Because the accident takes place in an underground station, we see the various characters travelling towards it. I tried to create a sense of real-time and urgency, despite the fact that the reader knows the accident happened fourteen years in the past.

Is there an important theme (or themes) that this story illustrates?

In fiction, there’s a temptation to try to undo the wrongs of the real world by applying logic, assuming that there is a single ‘truth’. In Smash All the Windows, I used several points of view, so that I could explore different reactions to and opposing viewpoints on the same subject. Who are the victims? Should individuals have been held accountable when large-scale accidents occur, or does this prevent the identification of the factors that create circumstances that allowed accidents to happen? How should families and friends of victims be treated when they’re searching for or identifying loved ones? Should those same friends and family members be allowed to participate fully in inquests? Of course, many of these themes were dealt with in great detail in the verdict of the second Hillsborough inquest, which is what set me on course for writing this novel. But it’s not a book about technicalities. It’s about human resilience, healing and art.

What did you learn about change and social classes in this book?

I learned that large-scale disasters are indiscriminate.

Who is/are the hero(es)? Who are the villains? And why?

Given that each character gets up day after day and faces the world, despite everything they’ve lost, all of the characters are heroic. It’s just that some forms of heroism are more obvious than others.

Gina Wicker didn’t only lose a son. She lost her idea of who he was – of who she herself was. She was not, as she had hoped, a good mother, and this knowledge led to a downward spiral of self-destruction. Is it any wonder that her daughter Tamsin is increasingly distant?

Tamsin finds herself at a crossroads. Almost twenty-seven years old, she’s still living at home with her alcoholic mother. But how long will boyfriend Graham wait? And having lost so much of her teenage years, isn’t she entitled to a life of her own?

Maggie and Alan Chappel aren’t from London. When Alan decides that the best chance he has of healing his hidden wounds is by returning to his Northumberland hometown, Maggie comes under mounting pressure to explain her reluctance to go along with his plans.

On that fateful day, two generations of Donovan’s family were wiped out in an instant. Not only his daughter and future son-in-law, but his unborn grandson. He has another source of pain, less obvious. One he cannot discuss. Ever since the funeral, his wife Helene has turned her back on the world, refusing to leave the house. But surely, if he can raise money to build a monument, she might be persuaded…

Jules Roche, unwitting poster boy for the disaster, has reluctantly found fame with the sculptures he created from an outpouring of blind anger and unending sorrow. Now, in celebration of the verdict, Tate Modern wants to stage an exhibition of his work. Jules accepts – but on his terms. And art created from anger holds the power to shock.

Of all of the characters, I think it’s Eric who deserves to be singled out. When most injustices are overturned, there is usually an individual in the background. The one who realised that an injustice had been done and who then worked tirelessly behind the scenes in order to construct a case. With the Hillsborough disaster, it was Phil Scraton, professor of criminology, whose credentials lent weight to the families’ arguments. With St Botolph and Old Billingsgate it was Eric, a law student who is still some way from qualifying as a solicitor.

The outsider in the story, his arrival proves to be a turning point for families, who have all but given up in their search for justice. In the midst of all of the heartbreak and human reaction, the unseen suffering, the unnoticed agonies, his conviction reminds the families that they still have a little fight in them.

The difference between Phil Scraton and Eric is that the majority of people are unaware of the role Eric has played. Save for the families, his efforts go unacknowledged. And while that might seem to be another injustice, he isn’t someone who craves the limelight. In fact, the reverse is true.

As for the villains? That’s a far more difficult question to answer. In the end, I decided not to make anger the only answer. I made my book about ‘unblame’ rather than ‘blame’.

Do the characters change?

The lives of the families of the victims have already changed in ways that they could never have imagined. Mostly, it’s a story about gradual healing, but there are breakthroughs and insights, some of which are critical. Maggie, in particular, has felt guilty about getting on with her own life. She has worried that this would mean forgetting. But Jules delivers a simple concept in a single sentence and you just know that it will kick-start the process of change.

Which character would you most like to invite to dinner this evening and why? Who would you invite too? What would you hope to learn?

I think it would have to be Jules. On the outside, he’s is a passionate, energetic and intriguing individual, quite anti-authoritarian, unafraid what people think of him, someone who makes you feel flattered when he unlatches the door to his world and invites you in. But like many artists, it is what’s behind the show of energy that is most interesting. I chose not to write about him in the first person, because I wanted to keep that sense of mystery about him, but I find myself wanting to learn more about him. (I’m slightly worried that he won’t like veggie stew and dumplings!)

Where did your research take you?

Apart from the incidents themselves, I researched the rapidly-changing demography of London, transport policy, accident investigation, crowd theory, crush injuries, obituaries, working on the Underground, the layout of Underground stations, working as a tour guide, working as a set designer for the stage, ghost stories, medical information. Art features quite heavily in the novel. Sculpture, modern art, and heaven and hell depicted in art. At Tate Modern, I specifically sought out works of art where what was written on the wall label dramatically changed the way I thought about it.

So many tiny details go into the making of a book. The rule of thumb is that research shouldn’t show up on the page, but Smash all the Windows is the exception. Eric’s hard-won logical deductions needed to be shown. Mapping out the chain reaction that led to the disaster became Eric’s obsession and he paid the price with his health. Because I only had to show snap shots, thankfully my walls weren’t covered in his crazy line-up of Post-it notes. I didn’t suffer the same headaches, the stressful late nights fuelled by copious amounts of caffeine.

What moments in the novel do you like best?

Some of Donovan’s scenes are among my favourites. Donovan is a big-hearted man, but one who finds it difficult to express his emotions. There’s is a moment when Donovan finds a pair of his daughter’s swimming goggles in the garage. They have lain there, undisturbed for over thirty years, but he finds them just after he makes the decision to allow Jules to have the pieces of wood from the unfinished crib he was making for his unborn grandson. (The idea is that Jules takes mementos from the families and uses them to create new works of art.) Donovan translates this as his daughter’s way of letting him know it’s OK.

I also like the moment that lent itself to the cover image: the starling. I borrowed a moment from one of my city walks. I was taking the stairs from the Riverside Path to London Bridge when I saw a starling sitting on a steel railing, singing its heart out. Hearing birdsong when surrounded by the traffic roar and the clang of building works is quite special and so I stood and watched. I used this moment for my character Maggie, who’s the mother of the young station supervisor who was in charge when the disaster happened. She feels her daughter is sending her a message.

So I think you’d have to say that my favourite moments are those in which people find ways to connect and communicate with their loved ones.

Have you compared Smash all the Windows to any other novels you’ve read? What’s the same? What’s different?

I hope it will be enjoyed by readers of How to be Both by Ali Smith and How to Paint a Dead Man by Sarah Hall. Both have much to say on fragile, precious and unpredictable life is. Both focus on what it means to be human and our innate connection with art. Neither is likely to put you off escalators.

Publication details

Smash all the Windows will be released on 12 April, but you can pre-order it now for the special price of 99p/99c (Price increases to £1.99 on 12 March. Price on publication will be £3.99). The Universal Link is books2read.com/u/49P21p

From 13 February to 10 March, US readers can also enter a Goodreads Giveaway for a chance to win one of 100 eBooks. https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/38447206-smash-all-the-windows

Thank you, Jane, for an intriguing glimpse into your processes.

For readers who would like to know more about Jane Davis and her work, please see her website and/or follow her on Twitter, Facebook, and Pinterest. This entry was posted in Guest Bloggers and tagged contemporary fiction, Jane Davis by Elizabeth Gates. Bookmark the permalink. January 9th 2018